On a gorgeous April Wednesday I am filling in as substitute homeschool teacher. We do arithmetic; we do a language lesson about adverbs and Emily Dickinson. Then—did I mention the day is gorgeous? That the air through the window is crisp and fills the lungs with hope and delight? That the cardinals are courting round the bay tree and a wren is chirping from the buckthorn? That the sky is blue, the dandelions gold, the violets… er, violet? All this is so, and the substitute teacher, less inspired by whatever lies in the plan book before him than by the season swiftly unfolding outside the window, calls an audible….

Ten thousand year tomorrow corn chowder

It is summer, and corn is coming into season. I am not ashamed to admit that I have a corn problem: When I see corn, I have to buy it. I buy a dozen ears, even if I have no idea what to do with them. And though I do love corn on the cob, I have my limits. Sometimes, too, corn deserves to be more than a side dish, slathered with butter, gnawed in and flossed out. Corn deserves a little love.

And so, today, we are going to make corn chowder. We are going to take our time about it. Corn chowder is a simple thing, which means that it deserves to be made carefully, thoughtfully, attentively, because it has no ornament to distract the senses, no frivolity or luxury to excite the mind. Simple food can be only what it is, and so it must be all that it is and should be, else it is not worth eating.

We will make enough to serve eight, because, presumably, we can find some friends to help us eat it. (If not, there’s always lunch.)

In further defense of scrapple

Doubtless some readers will have been puzzled yesterday by my use of scrapple as a model of purity. But, you know, there is scrapple, and then there is scrapple. There’s country scrapple and city scrapple, as the distinction used to be drawn, back when country people, or at least country butchers, still made their own. There was country panhaas, made by Pennsylvania Germans, and there was its bastard cousin Philadelphia scrapple.

Pink slime: Or, the whole scrapple

My main thought on all this horror over “pink slime” is that it doesn’t sound any worse than any food-like product I’d expect to come out of a factory. I mean, what do you expect? The goal of the U.S. food industry is to produce substances that are chemically compatible with the maintenance of human life and that are aesthetically and culturally palatable to American consumers, all at the greatest possible margin of profit. Pink slime, duly flavored with extracts, shaped into a patty, topped with half the contents of the refrigerator and eaten by a model with juice dribbling down her chin, pretty much nails it.

But I get tired of reading only people I agree with, so I went looking for contrary arguments.

Letting the flowers say it for themselves

I had to mow the grass today for the second time this year, an appalling side effect of global warming. (I know, I know: Entire countries are at risk of sinking beneath the ocean, and I’m complaining about mowing my grass an extra month of the year. It’s a first-world problem.) I didn’t think it looked all that bad — I could still see the tops of my shoes when I walked in it, and from my study window the dead nettle made a pretty sort of fuchsia haze over the yard — but with a reel mower you can’t let it get too long, and so I took my lunch break at yard work. With a reel mower, though, I can set the blade high enough to lop the tall weeds and reveal the lower-growing violets and the buttercups, which have crept through much of the back yard in the past few years.

Why plastic chicken is not the answer

Mark Bittman writes in this Sunday’s New York Times (“Finally, Fake Chicken Worth Eating”) that he has decided, at last, to endorse fake meat, because he believes that Americans ought to eat less meat and because certain new soy- and mushroom-based fake meat products are, in certain circumstances, nearly indistinguishable from industrially produced chicken breast.

On its own, Brown’s “chicken” — produced to mimic boneless, skinless breast — looks like a decent imitation, and the way it shreds is amazing. It doesn’t taste much like chicken, but since most white meat chicken doesn’t taste like much anyway, that’s hardly a problem; both are about texture, chew and the ingredients you put on them or combine with them. When you take Brown’s product, cut it up and combine it with, say, chopped tomato and lettuce and mayonnaise with some seasoning in it, and wrap it in a burrito, you won’t know the difference between that and chicken.

Bittman’s uncritical acceptance of the way Americans consume chicken breast, moreover — which is to say, mechanically — is disappointing from a man who has done as much as anyone to teach Americans how to cook and eat real food in simple, practical ways. There’s no indication that the product tastes good, only that it isn’t terrible. Nor does it promoting it in this fashion aid the cause of good cooking or of thoughtful, intelligent consumption. To embrace the consumption of “meatlike stuff” produced by a “thingamajiggy” is, I believe, to embrace the error at the root of modern industrial agriculture, and therefore, in the long run, to worsen its effects.

John Henry and the honeysuckle

So when John Henry retired from driving steel he moped around the house and he moped around the yard until Polly Ann shouted, “John Henry, why don’t you quit your moping around like a soggy pie and dig me a garden!” So John Henry picked up his shovel and he picked up his mattock and he started digging. But there was honeysuckle growing all over the fence, all up one side and down the other, and those vines ran underneath the ground from here to there and back again. John Henry dug from one end of the yard to the other, but everywhere he put his shovel, the honeysuckle vine reached up and snagged it. That honeysuckle snagged his shovel, it snagged its mattock, it even snagged John Henry’s foot. Ol’ John Henry put down his shovel and said, “Lord, that honeysuckle’s gonna be the death of me!”

What you can grow in Durham, 2011-12

Intrigued by Thomas Jefferson’s calendar of the Washington city market (see the previous post) and liking the design, I decided to use it as a model for mapping produce available right here, right now. So with some help from Erin Kauffman, market manager for the Durham Farmers’ Market, I compiled a produce calendar for Durham, North Carolina, 2011.

Distracted by the leavings of winter

A glorious day, warm and bright. Having time to spend, and wanting to feel hopeful for the changing of a season, I sat where I could see the first full blooms of spring — but found myself distracted by the leavings of winter. Unloved and unnoticed, these masses of grays and browns, bare rock and tree and mud and crumbling leaf. But examine them closely in the dusky light of a fading afternoon, and the tattered monochrome resolves itself into a deep-textured symphony of shape and line shaded from the palette of a master.

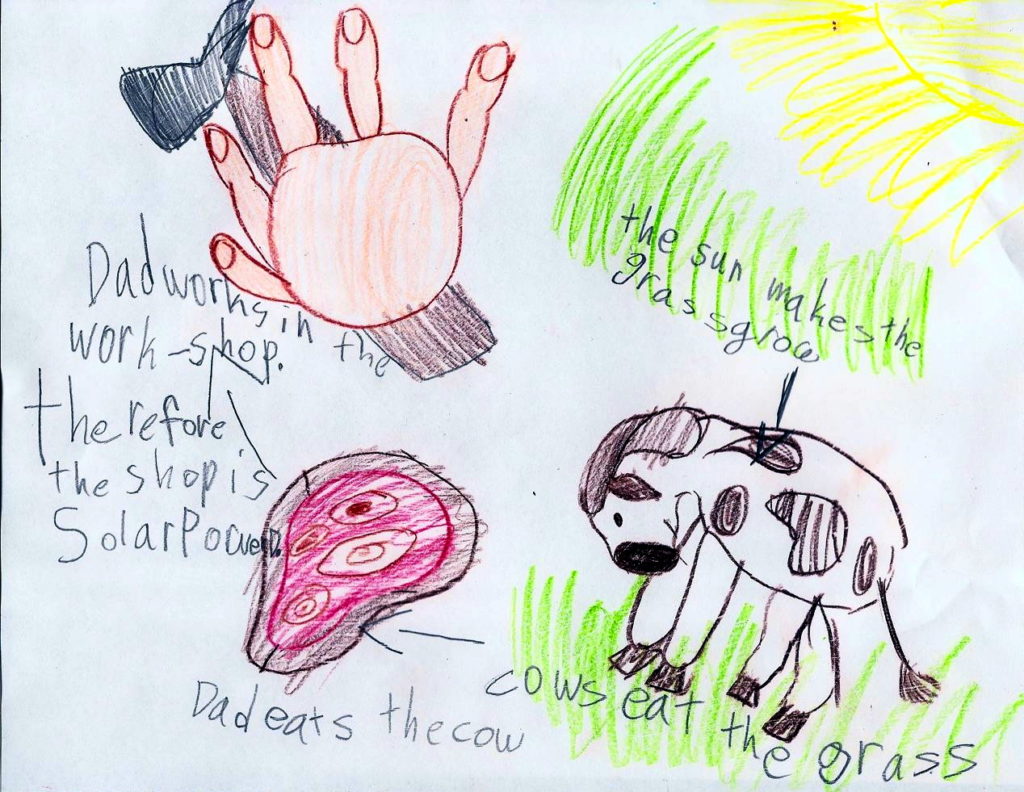

The solar woodshop, explained

These days it’s all green this and renewable that, solar houses and electric cars and trains that run on cow farts. Well, look, my woodshop runs on solar energy, too. My daughter drew this diagram to show you all how it works:

I admit I do run a fluorescent light and a radio. But otherwise it’s just the sun, grass, cows, and me. Ain’t no energy greener than hand power, friends.