A glorious day, warm and bright. Having time to spend, and wanting to feel hopeful for the changing of a season, I sat where I could see the first full blooms of spring — but found myself distracted by the leavings of winter. Unloved and unnoticed, these masses of grays and browns, bare rock and tree and mud and crumbling leaf. But examine them closely in the dusky light of a fading afternoon, and the tattered monochrome resolves itself into a deep-textured symphony of shape and line shaded from the palette of a master.

The solar woodshop, explained

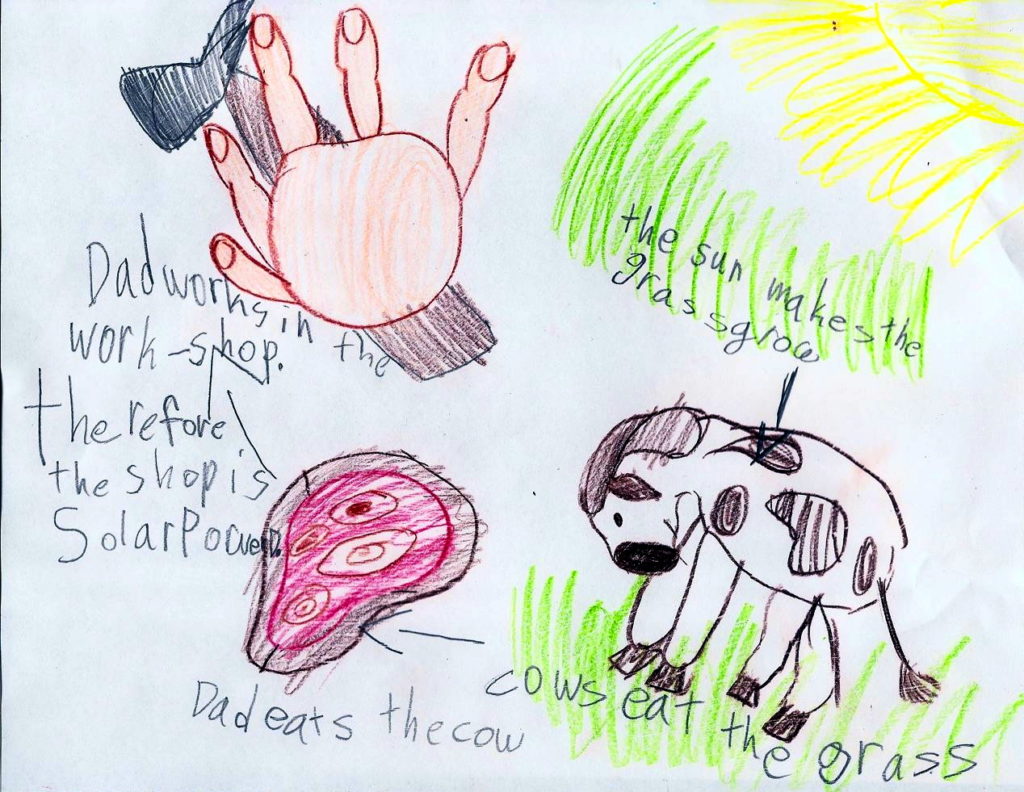

These days it’s all green this and renewable that, solar houses and electric cars and trains that run on cow farts. Well, look, my woodshop runs on solar energy, too. My daughter drew this diagram to show you all how it works:

I admit I do run a fluorescent light and a radio. But otherwise it’s just the sun, grass, cows, and me. Ain’t no energy greener than hand power, friends.

Jumbals

In researching historical baking I’ve ignored some old standards — very old standards, I mean, not like oatmeal cookies — and now that I have a lull in the research I’m picking them off. This month it’s jumbles, or jumbals, if you prefer the old spelling, which were formerly like nothing that goes by that name today.

Mindful, but still not gravied with conviviality

An article in today’s New York Times examines yet another case of Americans taking a fundamentally sound idea — mindful eating — and driving it to extremes. Having just concluded a draft of my book with an epilogue in which I urged not only mindful eating but (especially) mindful cooking, it pains me to say this, but, seriously, people: lighten up.

Candlemas

Tomorrow is Candlemas: the midpoint of winter, halfway between the solstice and the equinox, in cultures unspoiled by scientifically rational astronomy the first day of spring, and in much of Western Europe traditionally the day to break ground for the first of the year’s crops. Pagans had astronomy plenty to mark the day, often (plausibly, to celebrate the returning of the light) with fire. The Catholic Church, as it so often did, co-opted the festival for its own purposes, using the day to celebrate the purification of Mary forty days after giving birth to Jesus, the light of the world. And so Catholics brought their candles to the church to have them blessed, whereupon the candles became talismans that could be lit during storms or times of trouble, as an old English poem observed:

White-people soul food

I was intrigued by this article in today’s New York Times about “Mormon cuisine,” not because (as is the point of the article) it’s changing (what cuisine isn’t?) but because I had trouble seeing what was uniquely Mormon about any of it.

Making fresh noodles

A few years ago I bought some fresh pasta at the farmers market. (Well, frozen fresh pasta, anyway.) I asked how much it cost, and the lady said six dollars. Not cheap for plain noodles, I thought, but ok — let’s try the new business. I handed over six dollars. She handed me a six-ounce package of noodles.

That’s sixteen dollars a pound for noodles, y’all. Silly me, thinking I’d get a whole pound for just six bucks.

As I have since learned, it isn’t actually all that difficult to make fresh noodles. What’s difficult is making them look perfect. That takes equipment and space. But if you are willing to accept the style commonly known as rustic, you can make fresh pasta for a weeknight dinner. Seriously. You need a food processor, but you certainly don’t need a pasta machine. And depending on how you shape your noodles, it only takes about ten minutes of hands-on work.

What you could grow (and when) in 1800

Thomas Jefferson was a man of many interests, and being President of the United States doesn’t seem to have deterred him from pursuing them. If from the White House he couldn’t putter in his beloved garden at Monticello, he still managed to keep up with the business. During his eight years in Washington, he kept track in his journal of the produce available month by month at the city market and drew up a chart showing each item’s earliest and latest availability during his residence — a fascinating, if a bit foggy and bubbly, window into early American gardening and vegetable consumption.

Because I’ll not be out-geeked by a two-centuries-dead president, I’ve made an HTML version of Jefferson’s chart. His handwritten original was quite clever (you can see it at low resolution on the Monticello website) and I’ve preserved the basic design while adding a bit of interactivity: for now just the ability to mouse over headings to highlight rows and columns, but eventually also to view definitions and commentary on various items of produce.

Old news

On Monday I sheet-composted a rocky and shallow part of the garden, laid down newspapers to kill the weeds and spread old bedding from the duck pen on top. There is something deeply satisfying about heaping shit onto last week’s (now last year’s) news. A new dictator in North Korea? Shit on him. Elizabeth Dole endorses Mitt Romney? Shit on them both. Unemployment, debt, foreclosures, indefinite detentions? Pile it on! It’s old news. Most days the newspaper isn’t good for much, but it makes good drop cloths and weed barriers, and if politicians’ faces can crumble into next spring’s carrots, then they’re good for something too. Twenty-eleven is old news now as well, a year that seemed for me to brim over with crap, but amazingly fertile crap, as it all is, or ought to be. Old truths and new ideas spring from disillusionment. A finished book grows from the compost of a lost job. Bury last year deep, sheet compost the old bastard and baptize the new with mud. And a happy new year to us all.

Resolutions

Laugh at the vultures, who think you would steal

Their refuse. Love them anyway, and be grateful

For their meal. Say their grace.

Trade your house for a turtle, then set it free

In the woods, to find its way to water.

Rejoice in your hope.

Fall on your knees to see the wild flower

That grows in the ditch, its head erect

Among the paper cups and sandwich wrappers.

Then rise up. Go forth. Sing your song

As if you would make it so.

Work as if it mattered.