I created these maps for LEARN NC as part of a unit on industrialization in North Carolina to show why factories were built where they were. The map showing the location of textile mills was used in an exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History in 2011.

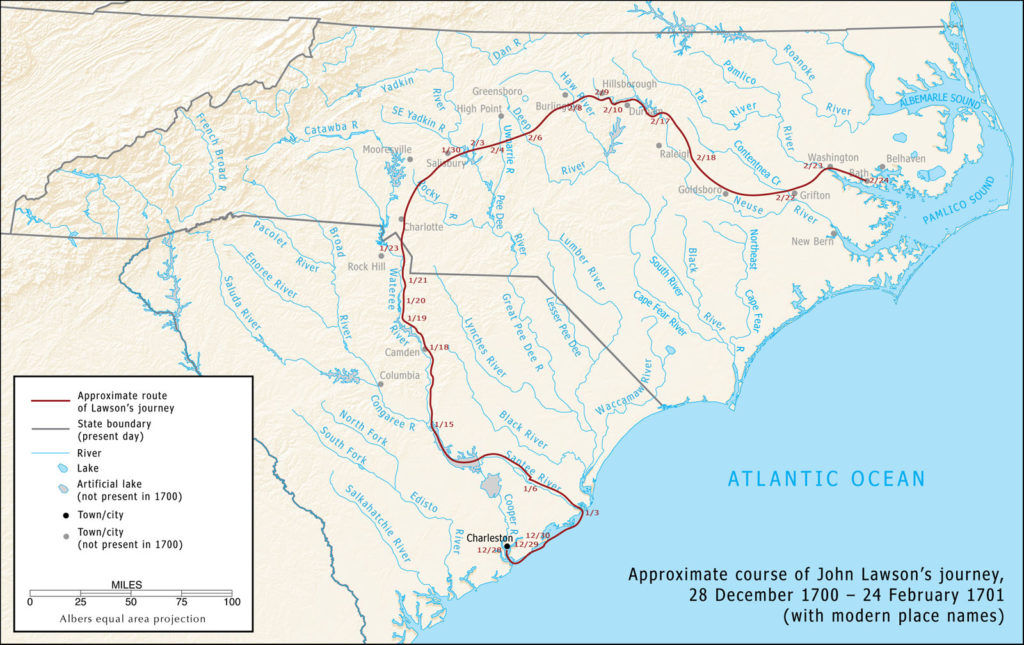

John Lawson’s explorations, 1700–1701

I created this map for LEARN NC in 2009 to show the approximate route of John Lawson, who explored the Carolinas in 1700–1701 and documented his travels in A New Voyage to Carolina (1709). I had intended the map to accompany a web-based critical edition of Lawson’s book, but I wasn’t able to finish the project.

I drew a new version of this map for The Curious Mister Catesby: A “Truly Ingenious” Naturalist Explores New Worlds, published by the University of Georgia Press in 2015.

A brief history of USDA nutritional advice

The USDA has made a big deal the last couple of years about its “healthy plate” model of good eating, which replaces the old food pyramid, which replaced the four food groups, which replaced… well… I thought a chart might help. Today’s post is a visual history of the USDA’s nutritional advice, showing how food groups and recommended servings have changed over the past century.

Sugar cookies with historical flavor

Sugar cookies can’t be too rich and buttery if you want to roll them, and the really good historical cakes and cookies aren’t cookie-like enough to pass for Santa fare. But we can mine those recipes for flavor ideas. Herewith, some historically plausible (1750-1850) flavorings for your Christmas sugar cookies that will kick them up a little without competing with the gingerbread. […]

Redistricting and electoral fairness: the view from Eno precinct

As if the election wasn’t annoying enough, I got redistricted this year here in North Carolina. I haven’t moved, but I’m in a completely different congressional district — or, rather, I will be when the 113th Congress convenes in six weeks or so. I wasn’t nuts about my future-former representative, and I like the new guy considerably less, but in the big picture, it doesn’t make much difference, because they’re both in Congress now, and they’ll both be in Congress come January.

But in the bigger picture, redistricting seems to have made a heck of a difference. Republicans won 9 of North Carolina’s 13 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives this month. Combined with the state’s vote for Romney, a newly elected Republican governor, and a re-elected majority in both houses of the General Assembly, North Carolina looks like a very red state, yes? In fact, Democrats won a majority of votes cast in North Carolina Congressional elections this year, even while winning less than a third of the available seats. Welcome to the wonderful world of partisan redistricting.

Details, research, and some history after the jump.

What’s “processed”?

Suppose you want to eat less processed food. Given how and what most Americans eat, that impulse is probably a good one. But once we go beyond the obvious (cheese curls, sugar cereal, hot dogs) you find yourself down the rabbit hole. What about that bottle of salad dressing you use to perk up your unprocessed salad? Is hot sauce ok? What boxed cereal can you eat? You start squinting over ingredients lists, blocking the grocery aisle with your empty cart. You accept an invitation to a potluck and sit horror-struck by the potential dangers lurking in the dishes, feeling your appetite slipping away like blue cheese dressing off a greasy wing. To bolster your flagging courage, you read endless blog posts about why the things you’ve given up are killing other people’s children. You develop an evangelical zeal, gnawed by the fear that your friends will make fun of you the moment you step out of the room. You begin to wonder if you should get new friends.

And then you throw up your hands and dive into a bag of Doritos.

Now, I am the last person to advocate eating most of the food available in American supermarkets. I make my own jam and pickles, I bake bread, I cook practically every meal from scratch, I shop at farmers’ markets. After twenty years of living and eating like this, industrially processed food no longer really tastes like food. Forget health concerns; it just isn’t particularly satisfying.

But having lived this way for twenty years — and having put a great deal of thought into it during that time, and having done a lot of research on how foods were historically prepared — I’m painfully aware that any notion of purity about this business is foolishness. Cooking is, after all, processing, and humans have been doing that for what, fifty thousand years? We’ve been grinding grain into meal for five thousand years, and we’ve been processing and selling food commercially (mainly as grain, oil, and spices) for probably four thousand. I can, if I try, justify the natural origins of practically any edible substance — or find fault with the freshest of fruits. (What the heck is “food-grade wax”?)

Obviously, any sane and sensible person is going to draw a line somewhere. But any line we draw will to some extent be arbitrary; any principle we set will inevitably include some things that seem thoroughly unnatural and exclude others we can’t manage without. I’m going to consider some possible standards, suggest an alternative that’s (you won’t be surprised to learn) largely historical, show how difficult it is to apply even that comparatively objective standard — and then draw some conclusions about navigating this mess sensibly. It’s a long piece, but hit-and-run easy answers are exactly what we need to avoid.

A diversity of gardeners

An article in last month’s National Geographic examines the loss of genetic diversity in the world’s crops, and this infographic, in particular, has been making the rounds of the Internet, at least in the corners where foodies and activists lurk. It shows the decline in diversity of common American garden vegetables between 1903 and 1983: more than 90 pecent of the varieties in existence at the turn of the twentieth century are now long gone. That loss of diversity has consequences beyond our inability to sample the flavor of a long-lost apple: with so little genetic stock available, changes in climate or a new disease might easily wipe out an entire crop, such as wheat, and we’d have no way to rebuild it.

It’s a lovely graphic, well designed and (if you aren’t already familiar with the issue) appropriately shocking. Like too many such graphics, though, this one doesn’t inspire much beyond despair. What can I, or anybody, do about it? The accompanying article gives the answer: I don’t have to do anything, because there are institutional “seed banks” working to preserve the genetic stock still remaining on the world’s farms. I’ve been shocked and then duly comforted; no need to get out of my reading chair. Let the experts handle it.

Except that this isn’t the right answer, or at least isn’t enough of one. Seed banks, valuable and worthwhile as they are, can only preserve the remaining — let’s say, as a round number — ten percent of the genetic diversity that once existed. But that ten percent is dangerously little. And institutions and experts can’t rebuild the remaining ninety percent, because they didn’t build it in the first place.

Jumbals

In researching historical baking I’ve ignored some old standards — very old standards, I mean, not like oatmeal cookies — and now that I have a lull in the research I’m picking them off. This month it’s jumbles, or jumbals, if you prefer the old spelling, which were formerly like nothing that goes by that name today.

What you could grow (and when) in 1800

Thomas Jefferson was a man of many interests, and being President of the United States doesn’t seem to have deterred him from pursuing them. If from the White House he couldn’t putter in his beloved garden at Monticello, he still managed to keep up with the business. During his eight years in Washington, he kept track in his journal of the produce available month by month at the city market and drew up a chart showing each item’s earliest and latest availability during his residence — a fascinating, if a bit foggy and bubbly, window into early American gardening and vegetable consumption.

Because I’ll not be out-geeked by a two-centuries-dead president, I’ve made an HTML version of Jefferson’s chart. His handwritten original was quite clever (you can see it at low resolution on the Monticello website) and I’ve preserved the basic design while adding a bit of interactivity: for now just the ability to mouse over headings to highlight rows and columns, but eventually also to view definitions and commentary on various items of produce.

Ye Olde Worcestershire: Eliza Leslie’s Scotch sauce, 1837

For Christmas dinner I wanted to try something historical — besides the cookies, I mean, and other than a plum pudding, which nearly killed me the one time I tried to eat it after the full-on holiday feast. The centerpiece was roast beef (top sirloin, which is nearly as good as prime rib and about a third the price per pound of actual meat), and heaven knows people ate enough beef in the nineteenth century. What did they put on that beef? Well, how about Worcestershire sauce?